CANBERRA’S MIRACLE SURGEON ROSS FARHADIEH TALKS ABOUT LIFE, LOVE AND WHAT IT ALL MEANS

This article was first published by the Canberra Times on the 18th February 2017.

When The Canberra Times published the story last month of local plastic surgeon Ross Farhadieh’s remarkable efforts to re-attach the hand of a young car accident victim, there was plenty of praise for him, including all the way from the Yale School of Medicine in the United States.

Arash Salardini, now an assistant professor of neurology at Yale, was a fellow medical student with Farhadieh at the University of NSW in the mid-1990s, and remembers him well.

Canberra surgeon Ross Farhadieh says being a doctor is the best job in the world. Photo: Brook Mitchell

“Every one of us knew he was going to be something great and expected him to end up in the Ivy League, except that he had a particular love for the Australian lifestyle,” Salardini says.

“I left Australia in 2006 after the race riots [of 2005] fearing for my safety and wanting my children never to have to apologise for the colour of their skin or their cultural origins. He had no intention of leaving, [telling me]: ‘There are idiots everywhere, but I love these people and the country they have built.’ It is nice to see he is getting some love back.”

So much is conveyed in those few short lines about the migrant experience and the contribution to Australia by people such as Farhadieh and Salardini.

Urbane, charismatic, charming – with a little bit of George-Clooney-salt-and-pepper appeal going on (and Clooney was another Dr Ross in ER, if you remember) – Farhadieh is about as far as possible from the stuffy, aloof stereotype of the surgeon.

He has private cosmetic surgery clinics in Sydney and Canberra where he does the usual facelifts, breast augmentations and nose jobs. He also works as a visiting medical officer in the public health system, training up-and-coming doctors and performing surgery on patients such as young Sarah Hazell, whose right hand was severed in a car accident but re-attached by Farhadieh in an epic 14-hour operation at the Canberra Hospital.

It’s not hard to see how he could as easily talk to a society matron about a facelift or a child about a split finger – he has the gift of being able to create an instant rapport.

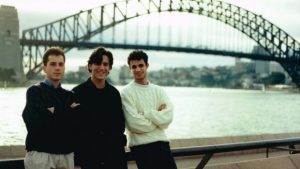

Ross Farhadieh (centre) in 1993 during his medical school days, sporting era-appropriate hair. Photo: Supplied

“I enjoy it,” he says, with his trademark enthusiasm and wide grin.

“I think the best part of medicine is the rapport. It’s not always possible. There are the odd patients who are pissed off with you, for whatever reason. But actually the vast majority of people, if you sit down and talk to them, you realise you can find common ground.”

Ross Farhadieh and wife Yasamin Farhadieh in Sydney, where they live while also spending time in Canberra, where he works as a surgeon. They are expecting their first child in April.

Taking off his well-cut suit jacket to reveal rolled-up sleeves, Farhadieh, 42, has a lightness of touch that belies his professional qualifications and the hard work that got him there.

Two degrees. Thirteen years of plastic surgery training. Fellowships to esteemed hospitals, including in paediatric plastic surgery at the famed Great Ormond Street Hospital in London. Editor of a major textbook on plastic surgery. Lecturer at the Australian National University’s medical school.

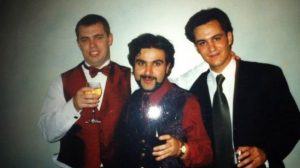

Ross Farhadieh (right) at medical school at the University of NSW with classmates including Arash Salardini (middle), who is now an assistant professor of neurology at Yale.

Oh, and he’s just enrolled to study Sanskrit at the ANU, for a bit of fun and relaxation in his spare time.

There’s more than an element of the romantic about him. He asked his wife, British anaesthetist Yasamin, to marry him on their first date. (And she said yes after knowing him only a few hours – more about that later.) He loves reading Persian poetry and watching classic movies. He sits down to Casablanca at least once a year. He enjoys life.

A bond for life: University of Canberra student Sarah Hazell had her right hand re-attached by Ross Farhadieh in what he believes was the procedure of his career.

With a father who was a civil engineer and a mother who was pharmacist, Rostam Farhadieh was born in Iran and moved with his family to Australia initially for a year as a 10-year-old and then permanently as a 14-year-old.

He has a younger brother who is a partner in a law firm in New York.

Ross Farhadieh asked his wife Yasamin to marry him just hours after they met (she agreed).

“It’s a long journey, if you think about it, a couple of kids from Tehran who ended up in Australia at the top of their professions,” he says.

“I don’t think we’re particularly smart but I think it was the work ethic put into us by our parents. You see the epitome of that in this country – if you work hard, you can get anywhere.”

A very cute Rostam (“Ross”) Farhadieh as a child in Iran.

With so much discussion about migrants across the world, Farhadieh obviously has his own thoughts. He doesn’t believe in assimilation – that migrants should abandon all traces of their home country.

“But I also believe in integration. You move to a place because wherever you were before wasn’t quite right,” he says.

Canberra plastic surgeon Ross Farhadieh and wife Yasamin Farhadieh on a trip to Italy.

“The best way to think about immigrants is you’re a seed of something but it’s the ground that you land in that helps you flourish.”

The family lived in relative comfort on Sydney’s North Shore, his parents keen to give their boys a more stable environment to grow up after the Iranian revolution.

“The driving force was my mother. She’s an ardent feminist. The picture of independence. My dad died when I was 17 and my brother was 15.”

He attended Gordon Primary School and Killara High School. “Elle Macpherson went to the same high school, that’s our claim to fame. I still remember seeing pictures of her thinking: ‘If I’d only come a few years earlier I would have had a shot,’ ” he says, laughing and then shaking his head. “Teenage boys – they don’t understand anything!”

He remembers struggling with English initially but being accepted socially pretty much straight away.

“The kids were remarkably good. They gave me a cricket ball and I’d never seen a cricket bat or a cricket ball and the first thing I thought was: ‘Christ, this ball’s pretty hard, if it hits you, it hurts.’ ”

He studied medicine at the University of NSW and found there were students from both privileged and modest backgrounds. He felt it was amazing to see the migrant kid from Bankstown get the same opportunities as the child from a private school in the eastern suburbs. To an extent. It wasn’t all heart and flowers. And top surgery appointments in Australia can still be a closed shop.

Farhadieh says he has experienced racism and the effects of the tall poppy syndrome at times.

“It’s a strange thing. It’s not just racism. It’s cliques,” he says. “Nothing cemented this in my head more than when a guy in my year, whose parents were first-generation Chinese, told me in a very broad Australian accent: ‘Look, you just have to accept you’re not part of the club.’ And therefore the plum jobs at St Vincent’s or Royal Melbourne aren’t going to be for me. And I thought: ‘Isn’t that a funny thing for a child of migrants to say?’

“I hear the same thing a lot. I had a conversation with a very senior surgeon, lovely man, good teacher, excellent operator and he’s Chinese. And he said to me: ‘You know, my training was very difficult. They wouldn’t give me a job because I was Chinese. But eventually through hard work, I toiled, I made it and that’s what immigrants have to do.’

“And I thought: ‘Well, not really.’ You work hard enough, in this country eventually there’s an opportunity for you. We have recourse to the law. And I don’t think the colour of your skin matters.”

So what kept him in Australia when university classmates such as Salardini went elsewhere in the wake of the Cronulla riots? (Salardini, also Iranian-born, was working in a hospital near Cronulla at the time of the 2005 riots and says “honestly. I did not feel safe”.)

“I know there are some idiots [in Australia],” Farhadieh says. “The key is everyone should respect the laws of our society. We have a liberal-democratic society, which is based on the equality of men and women and the equality of all before the law. You accept these things, brilliant, you’re a citizen. You don’t accept these things, then you might have to consider this is not the place where you might want to live.

“It’s not about banning Muslims or Jews or Christians. It’s about the values.

“I owe everything to Australia, it took me in and let me grow. I want my kids to grow up here and nowhere else. This country was built on hope and optimism and not fear and bigotry, and it’s up to all its citizenry to champion these in their lives every day.

“I tell our young registrars at every opportunity that it is vital to stand up and fight for what is right, irrespective of the cost, because that is what makes a good and compassionate society.”

Farhadieh says he always wanted to study medicine, inspired as much by two uncles and a family friend who were doctors as by Hawkeye Pierce on MASH, “the surgeon with the social conscience who walked to the beat of his own drum”.

“It’s the greatest profession in the world. People come and see you and they shed everything at the door and you get the privilege to sit down and talk to them and occasionally you get to help them too, right? And they let you do things to them.

“Every day that someone lets an anaesthetist put them to sleep, for me to put a knife to their skin, I’m amazed at the level of faith and trust that they’re showing me and I feel anything less than the best I could do would be letting them down.”

Among the surgeons he trained with and who became mentors to him were famed medicos John Crozier and Wayne Morrison. Farhadieh sent his young Canberra patient Sarah Hazell to Morrison in Melbourne for further work after he saved and reattached her hand.

“There’s a few people who, when you go through life, actually want you to do better and be better,” he says.

“John and Wayne are definitely among those guys you want to look back and think: ‘The time they invested in you, it was worth it.’

“I love Star Wars and always refer to Professor [Morrison] as the Yoda of plastic surgery, as do all our registrars. The force is strong with him. I always joke with him that he is Mick Jagger’s age and is like the Mick Jagger of plastic surgery:a superstar that gets better with age.”

Farhadieh and Yasamin are expecting their first child in April. He says it’s “humbling” to be on the other side of the equation, a patient in the hands of the medical profession. Putting your hopes and dreams and faith into a doctor to deliver the best outcome.

The couple married in 2014 after meeting at a hospital in London where she was working as an anaesthetics registrar and he was compiling his textbook, speaking to more than 100 plastic surgeons around the world. They met in a corridor of the hospital, the introductions a blur as he was struck by her beauty.

“The moment I met her I knew. I was just looking at her going: ‘Have to ask her out, have to ask her out, have to ask her out.’ ” he says.

“So eventually, I built up the courage and said ‘listen can I have your number?’ because I was worried if she walked away I was never going to see her again.”

They agreed to meet that afternoon after work.

Yasamin says there was an “instant attraction” when she met Farhadieh.

“We went out to dinner and we didn’t end up eating anything as we were talking so much. They kept coming up and asking us to order and we kept saying ‘later, later’,” she says.

“Later in the night, he said ‘would you consider becoming my wife?’ and I said ‘yes, of course’.

“We weren’t drunk, we’d hardly touched the wine. Later that night he texted me and said ‘I’m serious’ and then he rang the next day and said ‘I meant what I said’ and I said ‘I meant what I said as well’.”

Yasamin says she was usually a cautious person who had carefully thought out all the big decisions in her life. Agreeing to marry someone just hours after meeting them and then moving to the other side of the world with them was not on her radar.

“It was certainly against my nature to say ‘yes’ but it was instinctive. It was a no-brainer,” she says. “I was bold enough and old enough to understand the essence of someone when you first meet them.

“Ross is an incredibly passionate, principled, righteous man. Even if it puts him at a disadvantage, he will always do the right thing and he’s been like that throughout his life.

“But many people have those attributes. I love Ross because he’s Ross. There’s something about him that you can’t quite put into words.”

He, of course, has no regrets; friends often remind him he’s “punching above his weight”.

“It’s the best thing I’ve ever done. She’s an amazingly compassionate human being who totally grounds me when I see her and I realise: ‘This is what it’s about, right?’

“You live in a nice society, you have your health, you have your job which is nice, you have a wife you love and they love you and a family. What else could you ask for? A long life! A long life.”

And they are looking forward to the next chapter. “I think he’ll be an amazing father. I think he was born to be a father,” Yasamin says.

On the day of Sarah Hazell’s operation, Farhadieh had the day off and was about to watch the latest James Bond movie. He instead got the call and went into surgery from Sunday evening to Monday morning, 14 hours in all. He missed his planned phone call to Yasamin, who was still finishing her training in London. As the hours ticked by, she started to worry and finally spoke to him on the Monday morning.

“He just said ‘I’m completely exhausted’ and couldn’t really say much else as I think they were organising the transfer [of Sarah] to Melbourne,” Yasamin says.

“Later that day, I spoke to him and he said ‘it’s the biggest case I’ve ever had’. And he was incredibly moved about it. He just kept saying ‘I hope this hand survives’.

“In my work, I’ve seen the dedication surgeons have and I’d like to think the majority care deeply about their patients but I don’t think I quite understood the extent of that until I met Ross.

“He will bring his work home, it’s impossible not too. It will be 10 o’clock at night and he’ll be saying ‘I hope this patient is all right’ and he’ll ring up and check. He cares so much about his patients.

“It’s not a job, it’s a lifestyle, a way of life.”